Want to make a public comment on the FAA’s proposed Remote ID rule?

Keep reading for some background on the rule or jump straight to our four major points to consider when writing your public comment.

Ready to make your comment? Click here to visit the FAA Register. If you have any questions, click here to join our community forum discussion.

Background on the Proposed Remote ID Rule

If you’ve been following the Remote ID conversation and want to make a public comment before the window to do so closes on March 2, 2020, this article is for you.

Since the FAA shared its proposed rule on Remote ID on December 31st, 2019 we’ve seen a deluge of articles on the topic—most of them negative—written by various stakeholders throughout the drone industry.

We’ve also seen over 9,000 public comments made on the Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NPRM) for the rule to date, which is where people can submit their opinions and concerns to help guide the FAA’s decision making.

But in spite of all this writing, navigating the different factors to consider for writing a public comment on the Remote ID rule might seem pretty overwhelming.

So how do you sift through all the noise and write a public comment that could actually make an impact?

Read on for our four major points to consider when writing your public comment.

Need More Information?

Feel like you need to learn more about the Remote ID proposal and the NPRM process before you start writing your public comment?

We’ve provided extra information at the end of this article to help get you up to speed:

- What are the details of the Remote ID rule?

- What is an NPRM?

- Why do public comments matter on NPRMs?

- Best practices for making public comments

Four Major Points to Consider When Writing Your Public Comment

First, understand that the way you write your comment is really, really important.

If your comment is poorly written, not well thought out, copied and pasted, or amounts to little more than a rant then there’s a decent chance it may be ignored by the FAA. In fact, if you read between the lines, the FAA basically says that comments like these will not be considered in their recommendations.

[If you’re looking for further guidance on how to write a good public comment for an NPRM, check out this section on best practices below.]

Here are our four major points to consider when writing your public comment on the FAA’s proposed Remote ID rule.

1. Cost

This proposal establishes design and production requirements for two categories of remote identification: Standard remote identification UAS and limited remote identification UAS. Standard remote identification UAS would be required to broadcast identification and location information directly from the unmanned aircraft and simultaneously transmit that same information to a Remote ID USS through an internet connection. Limited remote identification UAS would be required to transmit information through the internet only, with no broadcast requirements; however, the unmanned aircraft would be designed to operate no more than 400 feet from the control station.

– From the FAA’s NPRM “Remote Identification of Unmanned Aircraft Systems” (Executive Summary—Introduction and Overview—Paragraph 4)

Based on the above information, drone pilots will have two options for Remote ID compliance (a third option for hobbyists is to fly in an FAA Recognized Identification Area (FRIA)—see below for more information):

- Standard Remote ID: Broadcast ID and location directly from UAS and transmit the same information to an Unmanned Service Supplier (USS) simultaneously via the internet

- Limited Remote ID: Transmit ID and location through the internet only

Here are some points to consider related to cost for the two options detailed above:

- Replacement costs. Some drone models already on the market are not equipped for internet connectivity. This means that those drones either need to be retrofitted to do so or that drone pilots must buy a new drone in order to be compliant. For either of these options, the individual drone pilot shoulders the entire cost.

- Increase in drone prices. Adding internet connectivity and other required features, like the ability to more accurately gauge and report altitude, could lead to burdensome increases in manufacturing costs for drones and drone equipment. These costs will then be passed on to the individual drone pilot.

- Remote ID subscription costs. Under the new rule, drone pilots would be required to pay for a subscription service with one of the Unmanned Service Suppliers (USS) Although the FAA estimates that this subscription will only cost $2.50/month or $30/year (these amounts are taken from current LAANC subscription costs), the cost would in fact be up to the discretion of the third party and could increase at any time.

- Fee hikes. In addition to increasing the cost for subscription services at any time, USS companies could also impose fee increases for time of day, type of operation, flight location, etc. since there are no standard pricing requirements in the proposed Remote ID rule.

- Unforeseen infrastructure costs. As DJI has observed, companies providing USS services may need to invest in complex infrastructure to provide the “low latency and high security” systems required to support USS. These costs will almost definitely be passed on to drone pilots.

- Data costs. For drone pilots using cell phone data to transmit remote ID messages, there could be an increase in their monthly data costs.

- Mandated insurance. Some have expressed concerns that drone insurance could be mandated by USS providers, adding one more cost to the list.

- No rebates or subsidies. The FAA currently offers a rebate for newly mandated technology used on manned passenger planes to prevent collisions (called ADS-B). No rebates or other cost reduction initiatives have been included in the proposed Remote ID rule.

Possible Solutions

- Rebates and subsidies. Provide rebates, subsidized subscriptions, and/or other subsidies to reduce the burden on the individual drone pilot.

- Tax incentives. These incentives could be for drone pilots making the transition to Remote ID-compliant equipment, for manufacturers faced with higher production costs, or for other costs incurred by stakeholders transitioning to the new system.

- USS oversight. Create some kind of regulatory language or oversight for USS providers to prevent UAS type or platform exclusions, rate gauging, and ensure predictability about services and associated rates.

- Infrastructure planning. Include planning to address the unknown nature of the infrastructure that might be required for implementation of the current proposal, including concrete plans for helping to fund the costs for transitions to ensure that the bulk of these costs aren’t passed on to the individual consumer.

- Consider alternatives. Radio broadcast seems like a strong alternative to the network-based approach used in the current proposal. Learn more about radio broadcast and how it could reduce Remote ID costs by jumping down within this article.

2. Compliance

The FAA is proposing to require persons responsible for the production of UAS with remote identification to declare that the UAS meet the minimum performance requirements of the proposed rule using an FAA-accepted means of compliance by submitting a declaration of compliance for acceptance by the FAA.

– From the FAA’s NPRM “Remote Identification of Unmanned Aircraft Systems” (X. Operating Requirements for Remote Identification—E. Valid Declaration of Compliance—First Sentence)

As illustrated in the quote above, the NPRM primarily focuses on compliance from a manufacturing perspective. It does not propose any initiatives for ensuring compliance by the end users—that is, the 1.5 million drone pilots who actually fly drones in the U.S.

In the U.S. today there are currently about 1.3 million recreational drone pilots and about 162,000 commercial pilots.

To put this another way, recreational pilots make up about 89% of all the drone pilots in the country.

This means that if recreational pilots are not compliant with Remote ID, it will basically be dead in the water.

We already know from experience that much of compliance with FAA regulations is a result of positive action—people proactively trying to do the right thing, as opposed to negative—people being punished for doing the wrong thing.

And the way the rule is proposed right now, it seems unlikely that most recreational drone pilots will be motivated to comply.

For example, if you are a recreational drone pilot who only flies every now and then, it seems unlikely that you’ll take the extra steps required to be compliant with these new rules.

Further, the FAA hasn’t included any proposals in the rule that might incentivize compliance, such as incentives that would allow for special types of flying, like flying at night or flying over people, or other financial incentives. Under the new rule, those drones that can’t connect to the internet—of which DJI estimates there are thousands currently in use, including many drones made from kits—would simply become illegal to fly.

It seems unlikely that recreational drone pilots will simply throw their drone away and buy a new, more expensive one so that they can be in compliance.

Even a free or relatively inexpensive software update might be hard to get people to do if there isn’t a plan to roll it out—getting 1.5 million people to take action will require a communications plan and promotional budget, not just the publication of a new rule.

Possible Solutions

- Reduce the cost. Making people pay for something that used to be free is hard. If the FAA can reduce the cost it will almost definitely help to increase compliance.

- Reduce the logistical burdens. How can the FAA make this transition easier? Cost is part of the equation, but so is considering technological alternatives to the current proposal altogether. Again, radio broadcast seems like it could be an attractive solution to help drive compliance, since it appears to be cheaper and easier to implement (jump down within this article to learn more about radio broadcast for Remote ID).

- Education planning. We’re not sure if the NPRM is the right place for this, but it would be reassuring to see a comprehensive plan from the FAA regarding how it will educate recreational drone pilots regarding Remote ID that covers not just how to do it, but why it’s important. If pilots don’t understand why they should comply—that is, that Remote ID helps keep everyone safer—then they may not feel compelled to do so.

Ready to make your comment? Click here to visit the FAA Register. If you have any questions, click here to join our community forum discussion.

3. Privacy

The remote identification message elements that operators would be required to transmit to a Remote ID USS under this rule would be considered publicly accessible information.

- From the FAA’s NPRM “Remote Identification of Unmanned Aircraft Systems” (XIV. Remote Identification UAS Service Suppliers—C. Data Privacy and Information Security—Sentence 1)

Based on the above statement from the NPRM, these “remote ID message elements” would be publicly available to anyone:

- The drone’s latitude and longitude

- The drone’s barometric pressure altitude

- The drone’s serial number

- The control station’s latitude and longitude

- The control station’s barometric pressure altitude

While it makes sense for this information to be available to law enforcement and other government agencies, allowing private citizens to know where pilots are (i.e., the location of the control station) while they are operating raises safety and general privacy concerns, especially for those pilots who operate regularly in the same areas.

Individuals who are disgruntled with a flight path passing over their yard, for example, could easily determine the location of a pilot and harass them in person for flying in a way that is legal.

Possible Solutions

- General encrypted access. Encrypt Remote ID transmissions but allow citizens who have demonstrated ‘good actor’ intentions to access them through an approval process as well those approved by the FAA or other authorized parties.

- Strict encrypted access. Encrypt Remote ID transmissions and only allow specific government agencies with a demonstrated need to access them.

4. Logistical Concerns

These are things like operational limitations imposed by the new technology, stumbling blocks to adoption—things that would make people not want to buy a drone in the first place—and the fact that the new rule relies on technology that has never been tested at scale.

[Note: No excerpt is included from the NPRM here since this section refers generally to the proposed rule and thus draws from several parts of it.]

Here is a list of logistical concerns raised by the proposed Remote ID rule:

- Untested technology. This kind of system has never been used or tested on a large scale, which could mean that unforeseen complications and corresponding costs could arise. These costs will most likely be paid by drone pilots.

- Limited range. For those operating under the Limited Version (see the three versions included in the proposal below) they would be limited to keeping the drone within 400 lateral feet from the control station (not Visual Line Of Sight), which many consider an undue limitation, especially for commercial operators.

- Internet connection. Making reliable internet a mandatory requirement for any drone flight means that flights in rural areas or places where the internet is temporarily out would be impossible.

- Emergency scenarios. Related to the above, a drone might be grounded during an emergency due to loss of internet connectivity, which could prevent a public safety agency from using their drone to collect vital intelligence during a fire or the search for a missing person.

- USS accountability. The proposed rule does not propose any guidelines for the oversight of USS providers, which means that there will be no accountability for bad suppliers who willfully or accidentally provide bad services.

Proposed Solution

In a recent article DJI details how a radio broadcast Remote ID solution could address all of the logistical concerns listed above, as well as concerns about cost, compliance, and privacy.

We should note that DJI has skin in this game, since they have created a radio broadcast Remote ID solution called Aeroscope.

But there is a reason DJI invested in the creation of Aeroscope—it’s because the FAA’s research strongly indicated that the future of Remote ID lay in radio broadcast.

That’s right. The FAA’s consensus research among industry stakeholders found radio broadcast to be a better Remote ID option than the network-based option the FAA is currently proposing.

Here is an excerpt from DJI’s article (the bold is ours):

In 2016, Congress instructed the FAA to convene industry stakeholders to determine how to accomplish Remote ID based on “consensus standards.” . . . the consensus recommendation was for drones flying under existing FAA rules to perform Remote ID via a radio broadcast, with network solutions an optional alternative. The ARC’s many months of work demonstrated how broadcast technologies scored best for inexpensive retrofit, ease of compliance, and performance. Network-based solutions involved the highest costs, burdens, and privacy intrusions.

Aviation officials in Europe, who also weigh the aviation safety and terrorism risks of drones, agree with that assessment. There, after much debate and thorough evaluation, the Remote ID regulation taking effect this summer requires a direct radio broadcast, not a network-based solution.

When drafting your public comment, consider asking the FAA why they have rejected the consensus of industry stakeholders about radio broadcast and are proposing a Remote ID approach that is more expensive and presents more privacy and logistical concerns.

Note: This concludes our four topics for consideration for those looking for guidance in writing a public comment. The remaining sections in this article provide general information about the proposed Remote ID rule and the NPRM process.

What are the details of the proposed Remote ID rule?

Remote ID refers to the ability to identify a drone at a distance using some sort of signal that transmits a unique identifier for the drone (think of a license plate for a car).

The FAA’s proposed Remote ID rule offers three avenues for compliance:

Standard Remote Identification (SRI)

The Standard Remote Identification (SRI) is the top category. It requires drone operators to use drone(s) and control station(s) of high quality with consistent internet connectivity. This option would allow the drone to send its Remote ID message to a provider that shares it with every stakeholder in an operation. The Standard option allows drone pilots to conduct normal operations under Part 107.

Limited Remote Identification (LRI)

The Limited Remote Identification category is for drone operators who do not have a reliable internet connection. Under this category pilots can operate on a limited basis, so long as the drone can constantly transmit the identifying message. The LRI category only allows for operations within 400 lateral feet of the control station. If something prevents the drone from sending the message it will not be allowed to fly.

FAA Recognized Identification Area (FRIA)

The FAA Recognized Identification Area category is for the recreational drone pilots who do not want to deal with Remote ID and just want to fly. The catch is that they can only operate in specific areas and must stay within 400 feet of the control station.

What is an NPRM?

NPRM stands for Notice of Public Rule Making.

This notice is required by law when an independent agency of the U.S. government (like the FAA) wants to add, remove, or change a rule or regulation.

After an NPRM is issued, the U.S. public has a certain amount of time to comment on the rule. Once the period for adding comments closes the agency then collects all the comments submitted and considers them as it works toward finalizing the new proposed rule or changes to existing rule(s).

Why do public comments matter on NPRMs?

NPRMs give each of us a chance to have a voice in the making of FAA and other government agency rules.

Whether you’re a hobbyist or a commercial pilot, the new proposed rule on Remote ID will impact you. We encourage you to share your thoughts on the rule by making a public comment.

Here is the FAA’s NPRM on Remote ID.

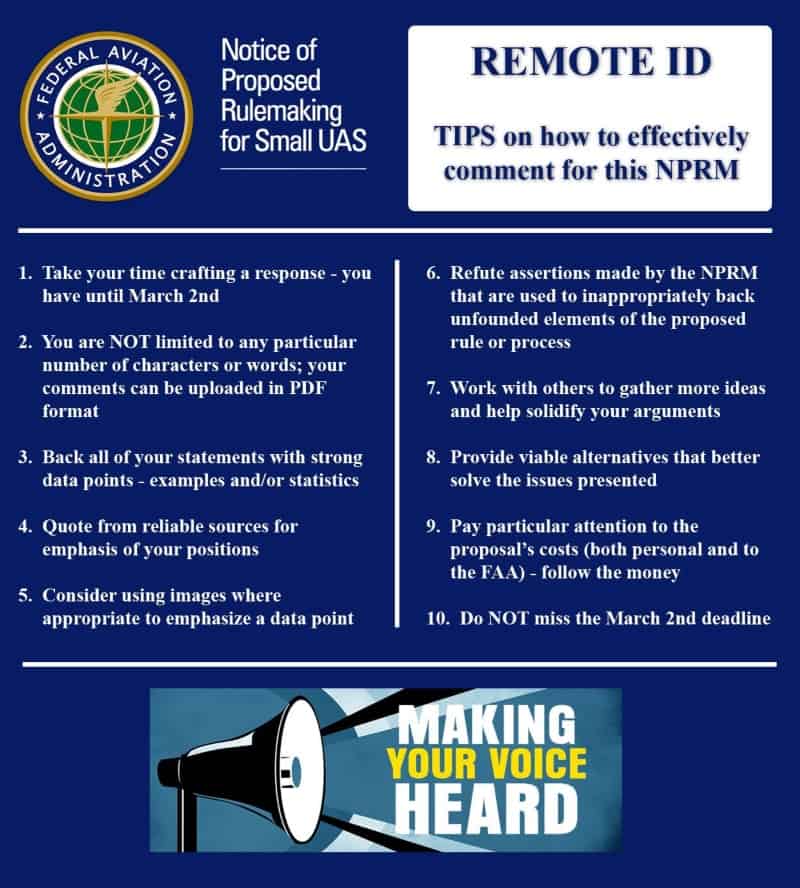

Best practices for making public comments

Here are some best practices for writing your public comment:

- Write your comment in advance. This will let you take your time and consider your thoughts clearly, without feeling rushed to hit publish. It will also let you share your writing with others to get their feedback.

- Propose alternatives. Don’t just say what you think is wrong with the proposed rule. Instead, propose alternative ideas that you think would work better.

- Avoid copy and paste. The FAA hasn’t said anything specifically about public comments that have been copied and pasted but we do worry that they may lump all copied comments into a single bucket, instead of considering them individually.

- Consider data and cost when making your points. Think of your comment as an argument—the stronger you can make it using data, examples, and/or statistics, the more likely it is that your comments will be heard. Also, don’t forget to think about the potential cost of what you’re proposing.

Ready to make your comment? Click here to visit the FAA Register. If you have any questions, click here to join our community forum discussion.

Here’s an infographic the FAA has shared with more guidelines to consider for writing your public comment: